When nothing seems to be happening in the garden, a lot is actually going on in the background. Right now we’re deciding how stable, productive, and relaxed the next gardening year will be: we look back at the past beds, loosen up dense raspberry areas, plant garlic, renew the mulch around our berries, observe the winter brassicas, and take care of soil and tools. At the end of this article, you’ll find a list of sources if you’d like to dig deeper into specific topics.

Table of Contents

Why winter is planning season for us

As soon as the garden visibly comes to rest, we switch internally as well – away from daily tasks towards reflection and structuring.

In winter we

take an honest look at the past season

plan how we’ll plant out the beds in the coming year

decide which structures have become too dense

and take care of soil, mulch, garlic, brassicas, tools, and everything that can be prepared calmly now

It’s not about a perfect master plan, but about a clear framework so we don’t have to make every decision on the fly once spring starts.

Instead of “The garden is done for the year,” our motto is: “Now we prepare next year.”

Looking back instead of feeling guilty

Before we plant or move anything, we sketch out the past season.

We keep it very simple:

a rough sketch of the beds on paper or digitally

short notes in each bed: what grew there, how the harvest went, any issues like drought stress, standing water, fungal disease, or heavy slug pressure

plus a quick look through summer photos to better judge density, height, and shade patterns

These notes are less of a “garden diary” and more of a work tool. They show us, for example:

which areas cause problems year after year

where we keep planting the same vegetable families in the same spots

and where soil structure has clearly improved

On that basis we build our crop rotation and next year’s plan. And if we ever forget where something was growing or what it was called, we can simply look it up again.

Crop rotation in the vegetable beds

For our vegetable beds we use a simple rotation logic:

We divide the area into beds or zones.

We group crops by family (for example brassicas, nightshades, cucurbits, legumes, root crops).

Each year every family moves on to the next bed.

This way, the same vegetable family doesn’t stand in the same spot year after year. That reduces the risk of soil-borne diseases and specialized pests, and helps keep nutrient supply more balanced over time.

At the same time, we roughly plan where heavy feeders, medium feeders, and light feeders will go, and we add quick follow-on crops where they fit (for example early radishes before warm-season crops, or green manure after potatoes).

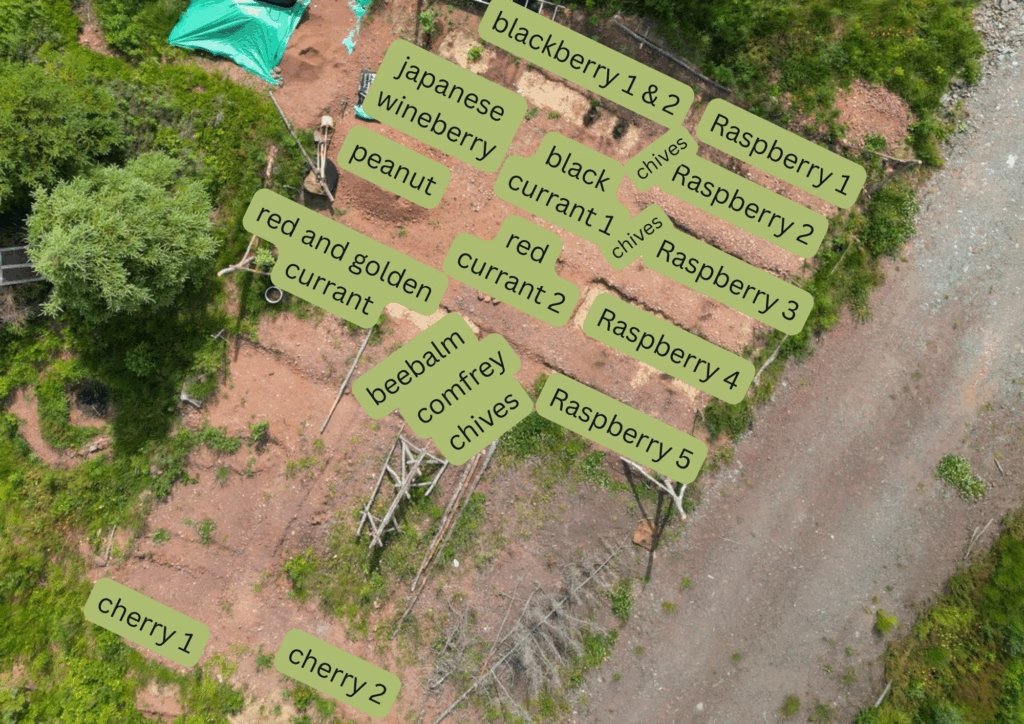

Loosening berry plantings instead of feeding monocultures

In one area of our garden, the raspberries showed us just how comfortable they felt: their runners had slowly formed a closed block.

At first that sounds great – lots of foliage, lots of harvest. But when one species grows too dense, we notice:

air circulation gets worse

fungal diseases have an easier time

the soil gets less light, less diversity, and fewer different roots

This autumn we took a deliberate look at our raspberry areas:

young, vigorous runners were carefully dug up

those plants moved to new locations where they can densify a hedge or build new structure

the original row was only thinned where it really made sense – older, well-placed plants were left in place

under the berry bushes we focus on ground-cover plants and bee forage that protect the soil and provide blossoms, without creating yet another solid “berry wall”

Quite concretely, this means the berries don’t remain on a single, matted strip but spread out across the property. In between, new spaces open up where ground cover, mulch, and flowers for insects can grow. Diseases and pests can no longer establish as easily in one continuous block.

Over time, this creates a loose belt of berries with a forest-garden character rather than a tight plantation – and we move a step closer to our goal of shaping the garden as a living permaculture space.

Transplanting and overwintering berries

With raspberries and other berry bushes we combined two things this autumn:

Loosening the structure

digging out runners in overly dense areas

moving young plants to new, intentionally chosen spots (for example as part of a future mixed hedge or as a privacy screen)

Preparing berries, other shrubs, and trees for winter

gently loosening old mulch without damaging roots

adding a fresh layer of organic material (leaves, partially decomposed wood chips, a little compost)

in exposed, windy, or frost-prone locations, adding straw over the root zone

The mulch protects the soil from erosion and temperature swings, holds moisture longer, and feeds soil life. We explain these connections in more detail in our article “The Art of Mulching – Sustainable Methods at a Glance.”

Knoblauch setzen, wenn der Winter schon anklopft

Planting garlic when winter is already knocking

This year our garlic went into the ground relatively late. Nights were already noticeably cooler, but the soil was still open and workable.

We’ve found a time window that works well for us, in which

the cloves can still put out roots

but the green shoots don’t grow too far above ground

Then the garlic rests quietly in the soil, is well rooted, and will shoot up vigorously in spring without being unnecessarily weakened over winter.

If you’d like to follow our garlic cultivation step by step, you’ll find all the details in our garlic plant profile and in our separate article on the blog about planting garlic.

Winter brassicas as site testers

Our winter brassica varieties have pushed out tender new shoots with the cooler autumn temperatures and shortening days.

We can read quite a bit from that:

If plants stand in a low spot and topple easily when it’s wet, the site was too moist.

If they grow on a slightly raised edge, stay healthy and compact, that points to a suitable soil structure and water balance.

These observations go straight into our planning:

problem spots get different crops or additional measures (for example drainage, more structure, or a different mulch strategy)

proven brassica sites remain reserved for brassicas within the rotation system

Winter-proofing beds: less tidying, more habitat

Our old autumn reflex was: cut everything down, clear everything away, reset beds to “zero.” By now, we take a different approach.

We distinguish between:

obviously diseased material (severe fungal infections, rotting parts), which we consistently remove from the bed

dead but healthy structures, which we let stand in many places

In practice this means:

seed heads and hollow stems stay in place in some areas – they provide food and shelter for birds and insects

leaves stay wherever they serve as mulch and winter protection: under shrubs, between perennials, around tree bases

on paths or surfaces we walk on in winter, we only tidy up as much as needed

This approach – less “clear-cutting,” more habitat – is also at the heart of the “Leave the Leaves” movement, which we refer to again in the source list.

Understanding soil – with and without a lab

For us, soil preparation doesn’t begin in spring but now.

We combine two perspectives:

At some spots we take soil samples and have them tested in the lab for pH and basic nutrients.

At the same time, we use our hands and eyes to see how the soil feels and behaves.

In “Soil Samples and Campfire: An Evening in Nature” we describe exactly how we took samples at different points, tested pH, and used those results to guide our first planting decisions.

Many agrarian and gardening recommendations also point to autumn as a good time for soil samples and pH adjustments – some of these are listed in the sources.

Even without lab tests, you can actively support your soil now:

- Observe soil structure

How easily can you loosen it with a digging fork? Does water sit in puddles for a long time or infiltrate evenly? How deep can roots grow without hitting compacted layers?

We share first pointers on this in “When the Soil Lives, Everything Thrives.”

Add organic matter

Where the soil looks tired, we spread compost, leaf mulch, or other organic material. How different mulch types behave is summarized in “The Art of Mulching – Sustainable Methods at a Glance.”When we use biochar, we “charge” it with nutrients before adding it to the soil. We explain the background in “Biochar – ancient wisdom, modern practice, living soil.”

Sow green manure while the soil still allows it

As long as the soil isn’t frozen solid, green manures are worthwhile: for example lupines or other legumes that root deeply and bind nutrients. A concrete example can be found in our plant portrait “Lupine”That way, the soil isn’t just “covered” in winter – it already receives impulses you’ll benefit from directly in spring.

Tools and water: the invisible part of winter work

The last part of our winter check may look unspectacular, but we feel it every spring when the season starts again.

We don’t have running water on our property yet. Still, for us – and generally for gardens with water supply – this block is part of the routine:

tools like spades, pruners, hoes, and digging forks are cleaned thoroughly, dried, sharpened where needed, and metal and wood are lightly oiled

garden hoses should be drained, coiled, and stored frost-free so they don’t become brittle or damaged by spring

where there are outdoor faucets, they should be shut off for winter and protected from freezing

Every year we notice how much trouble this saves: less rust, fewer dull tools, fewer damaged hoses and fittings.

Our winter to-dos at a glance

To wrap up, here’s what we’re actually doing right now:

sketching out the gardening year: what grew where, what yielded well, where were the problem spots?

roughly outlining crop rotation for the coming years – especially rotating vegetable families

deliberately transplanting raspberry runners and other berries to break up monocultures and create mixed structures

mulching berry areas and covering sensitive spots with straw

planting garlic as long as the soil is still open

observing winter brassicas and drawing conclusions for future planting sites

checking the soil – using lab tests where possible, and in parallel with simple home methods

adding organic material (compost, mulch, green manure) where the soil seems tired

removing only truly diseased plant material from the beds and otherwise leaving stems, seed heads, and leaves as targeted winter habitat

cleaning, sharpening, and oiling tools – and winterizing hoses and water lines

With steps like these, not only your garden grows – your sense of the land you’re working on grows as well. And that, in turn, is the foundation for every further layer of planning.

Sources and further reading

Our own articles

- The Art of Mulching – Sustainable Methods at a Glance

- When the Soil Lives, Everything Thrives

- Biochar – ancient wisdom, modern practice, living soil

- Lupine

- Permaculture and Forest Gardens: A Sustainable Path to Healthy Agriculture

- Soil Samples and Campfire: An Evening in Nature

- Garlic

- Planting Garlic Made Easy: Tips for a Bountiful Harvest

External expert and practice sources

- Utah State University Extension – Winter Garden Planning Tips

- UW–Madison Division of Extension – Fall is Best Time to Soil Sample Fields (PDF)

- Kellogg Garden – Winter Garden Planning 101

- Growing in the Garden – Winter Garden Planning in Mild Climates

- Xerces Society – Leave the Leaves!

- Nature Conservancy of Canada – Leave the Leaves

- 1000 Islands Master Gardeners – Leave the Leaves to Benefit the Web of Life

- Better Homes & Gardens – The Surprising Benefits of Leaving Fallen Leaves in Your Yard

- Burnett’s Country Gardens – Essential Fall Cleanup Tasks to Prepare Your Garden for Winter

- ND Landscape Services – Fall Garden Cleanup Checklist

- Gardenista – 6 Nature-Based Garden Tasks for Fall

- MyPlainview – Winterizing garden tools: Give your garden tools a winter spa day