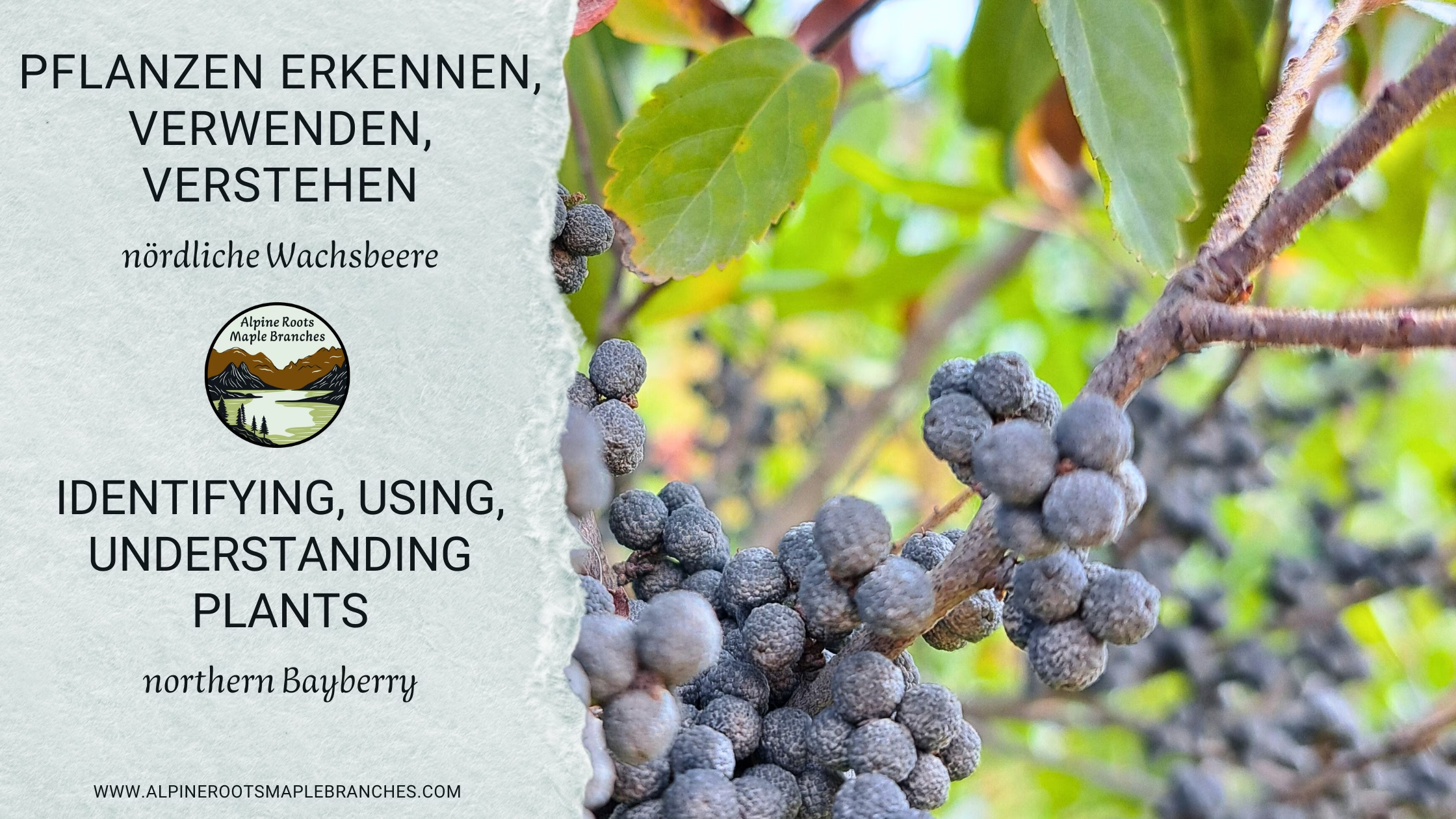

The Northern Bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica) is far more than a source of natural wax. As a hardy coastal shrub native to North America, it still thrives in sandy soils, endures salt spray and wind, and shapes dunes and forest edges along the Atlantic coast. Anyone who spends time with this plant soon discovers that it offers not only practical value but also a story deeply woven into cultural heritage and folklore. For an overview of its botanical features, ecology, and practical uses, see our Bayberry Plant Profile.

Early European settlers in North America learned to use the small, wax-coated berries to produce a pale green, aromatic wax. This wax was unlike anything they had known before — it burned cleanly, brighter than tallow, and filled rooms with a pleasant scent. Because the yield was low — many pounds of berries were needed for just one pound of wax — bayberry candles were considered precious. They were saved for special occasions, especially Christmas and New Year’s Eve. From this tradition grew a custom that survives today: a bayberry candle burned to the socket is said to bring luck and prosperity for the year ahead.

As the demand for the wax increased, regulations emerged to protect the plant. In several colonial communities, it was legally forbidden to harvest bayberries before September 15. The rule served a dual purpose: berries harvested later were fully ripe and yielded more wax, and the shrubs were given time to set seed, ensuring their regeneration. Today this can be seen as an early example of sustainable resource management, comparable to modern harvest restrictions designed to protect wild species. The fruits, which remain on the branches through winter, also continue to serve as an important food source for birds during colder months.

Birds still rely on bayberries as winter food, though only a few species can digest their waxy coating. The best-known is the Yellow-rumped Warbler, which evolved the ability to metabolize the wax and thus gains a survival advantage during food-scarce seasons. This unique ecological relationship between plant and bird demonstrates how the Northern Bayberry continues to shape its surrounding ecosystems.

The plant also held a place in traditional medicine. Indigenous peoples and later settlers used its bark, leaves, and roots to treat fevers, colds, digestive issues, and skin problems. While these remedies are no longer officially practiced today, bayberry’s aromatic and antiseptic properties remain appreciated in natural cosmetics, soaps, and incense.

Ecologically, the Northern Bayberry continues to play a vital role. Its roots form symbiotic relationships with microorganisms capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen, allowing it to thrive in poor soils while enriching the land around it. It provides both structure and sustenance in coastal and degraded habitats, where few other shrubs can survive.

In modern times, bayberry is experiencing a quiet revival. Those who value sustainable handcrafting can extract small batches of wax from the berries and blend it with neutral waxes such as soy or beeswax to produce long-burning candles with a subtle resinous fragrance. Even the water left from the extraction process can be used — as a compost activator that suppresses rot-causing bacteria and supports beneficial organisms. In this way, the Northern Bayberry beautifully connects traditional knowledge with modern sustainability practices.

If you’d like to explore its botanical traits, ecological functions, and home-use recipes in more detail, visit our Bayberry Plant Profile for a full overview.