We’ve largely forgotten what it takes to fill a plate. Every slice of bread starts with seed, soil, weather, and work. Every portion of tofu starts with beans, water, a mill, and a coagulant. Every sauce starts with a bed that must be tended, harvested, and processed.

This guide makes visible which nutrients a body truly needs—and how much area, diversity, and processing sit behind a year of consistent home-grown food for two adults.

Self-sufficiency doesn’t begin in the pot. It begins in the soil.

Table of Contents

Self-sufficiency isn’t a romantic slogan, but a chain of decisions: Which nutrients must be secured every day, which crops carry that load, how large are realistic field and storage losses, and how much area is required so that enough remains in the pantry at the end of the year.

We proceed step by step.

First, clear nutrient targets per adult, explained simply. Then we translate them into a realistic growing plan for two people, including grains for bread and pasta, beans and soy for protein, oats for yogurt, fruit, berries, nuts, and kitchen vinegar.

We deliberately prioritise diversity over monocultures, companion plantings to reduce pest pressure, and crops that perform in cooler climates.

The numbers are practical guide rails with losses included. They show what is truly necessary—not what one might wish for.

Why each crop earns its place

Nutrient targets determine the crop list. And the crop list determines how much land, labor, and processing are realistically required.

When it’s clear how much energy, protein, fat quality, and micronutrients are needed per year, the most efficient crops fall into place. Calorie-dense goals push potatoes, winter squash, and grains to the front because they store a lot of energy per square meter and per labor hour. A higher protein requirement steers planning toward dry beans, lentils, or soy—not only for protein content, but also for storability and the work needed to turn harvest into food.

Area follows from crop choice. Bread habits translate almost one-to-one into grain area, whereas a potato-heavy menu binds far less land for the same calories. If tofu is on the weekly menu, reserve soy area and kitchen time for milling, filtering, and coagulating. If porridge is a morning habit, shift area toward hull-less oats and plan for a flaker.

Crop choice also defines labor profiles across the year. Leafy greens and salads require frequent sowings and regular harvest windows, but repay with dense micronutrients. Storage crops like cabbage, carrots, and onions bundle work into harvest and processing peaks, then ease the winter. Tomatoes and peppers need protection, tying, and canning days, but repay the effort with sauce bases for bread toppings, pasta, and bakes.

Processing steps widen the gap between harvest weight and edible yield. Grain becomes flour only after cleaning, drying, and milling. Soybeans become tofu only after soaking, wet-milling, coagulating, and pressing. Fruit becomes kitchen vinegar only after fermentation and reliable acetification. Each stage demands time, tools, and know-how that must be built into the yearly workflow.

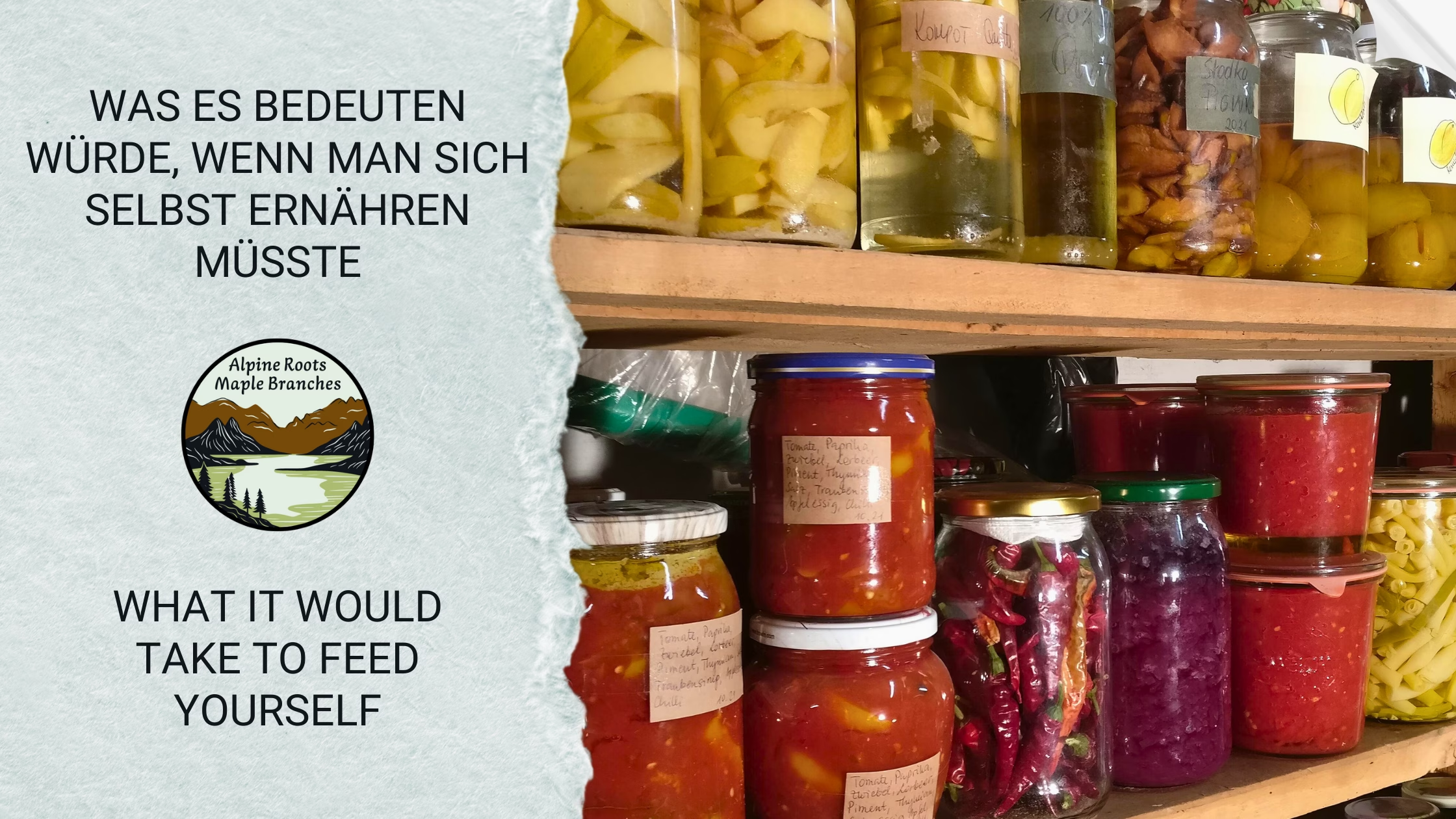

Risk and storage strategy also arise from crop choice. Mixed plantings and diversity spread pest pressure and weather risk, but reduce available row length per crop and require good spacings and companion plants. Storability decides how strongly winter relies on reserves rather than fresh harvest. Sauerkraut, net-stored apples, dry beans in jars, potatoes in a cool room, and bottled passata are not just products, but buffers against shortfalls.

Finally, site factors tie goals to realities. A windy, cool garden favors brassicas, leeks, and potatoes, but needs rain-shelter and warm niches for tomatoes and eggplants. Water access, soil reaction, and habitat for beneficials determine how repeatable yields are year to year. Only when nutrient targets, crop mix, area, labor windows, and processing fit together does a plan emerge that fills the plate not just in theory, but in practice.

Nutrient targets per adult

Before we dive into details, a quick why: nutrient targets aren’t diet rules—they’re signposts so that enough energy, protein, quality fats, and micronutrients actually make it onto the plate across the year.

They help allocate bed space sensibly, stagger harvests over the season, and schedule processing like fermentation or canning.

Values are ranges because age, size, activity, and climate differ—the key is direction and regular supply. With this frame, it’s clear why some crops get more space while others mainly add variety, flavor, and micronutrients.

Macronutrients – what are they?

Macronutrients are the big building blocks that power the body and build tissue. They shape most meal planning. The goal is to combine them so calories, satiety, and everyday cooking work together.

Energy

Reference per day: ~1,800–2,200 kcal for many women and ~2,200–2,800 kcal for many men (size, age, activity). In the garden, potatoes, winter squash, and grains carry most of the energy.Protein

Material for muscle, enzymes, repair. Practical floor: ≥ 0.8 g per kg body weight per day (70 kg ⇒ ≥ 56 g/day). Plant examples: beans, lentils, peas, soy, chickpeas, lupins—paired with tubers and grains for an everyday amino-acid balance.Fats

Energy carriers and transport for fat-soluble vitamins. The plant omega-3 precursor ALA matters; e.g., 1–2 tbsp freshly ground flaxseed daily or a handful of walnuts.Carbohydrates

Primary energy from potatoes, winter squash, bread and pasta; secondarily from roots like carrots or beets.Fiber

Supports digestion, satiety, and glycemic control. Broad coverage via legumes, whole grains, roots, and leafy/brassica vegetables.

Micronutrients – why they matter

Micronutrients don’t bring calories, yet they’re the switches and sparks of metabolism. Small amounts suffice—but they must arrive regularly.

Vitamins

Support cell protection, blood formation, immunity, and bone metabolism. Fresh sowings, gentle cooking, and lactic fermentation help preserve them.

Vitamin A (beta-carotene): squash, carrots, kale, spinach

B-vitamins (B1–B9): whole grains, legumes, leafy and brassica vegetables

Vitamin B12: can occur in some ferments (e.g., sauerkraut) but is variable and unreliable—supplementation or fortified foods are the practical standard

Vitamin C: berries, brassicas, peppers, fresh fruit

Vitamin D: often scarce in northern latitudes; plan sun exposure and possibly supplementation

Vitamin E: nuts and seeds

Vitamin K: herbs like parsley, and leafy greens

Minerals

Are structural elements and control points for nerves, muscles, and enzymes. Some come mainly from storage crops and whole grains, others from fresh leaves and herbs.

Calcium: bones, muscles, nerves; from calcium-rich greens, beans, nuts, seeds; fortified drinks where useful

Iron: oxygen transport; absorption from plant foods improves with vitamin-C-rich sides

Zinc: immunity and healing; broad in whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds

Iodine: thyroid; practically via iodized salt

Selenium, magnesium, potassium: widely from whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, vegetables

Growing plan for two people

Before the lists: we budget 10–20% field losses and 5–20% storage/processing losses. Yields are averages for a well-managed home garden, not record highs. Why the spread? Some harvest is lost to pests and weather in the field; more during sorting, drying, and storage (bruising, rot, moisture loss). Areas below are sized so the target usable amounts reach the kitchen despite these normal swings.

Calorie and storage staples

This group provides the reliable energy base: potatoes, sweet potatoes, winter squash, plus carrots, beets, and other storage roots.

The goal is bulk that stores well. Key levers: deeply loosened, stone-free rows, adequate potassium and boron, consistent mulching to reduce evaporation, and harvest timing that respects skin set.

After harvest comes curing: sweet potatoes warm and airy for a few days, squash 10–14 days in dry warmth, potatoes dried off in the dark and cool.

Store in clean, well-ventilated, frost-free rooms; indicative temperatures 10–14 °C (sweet potatoes), 8–12 °C (squash), 2–6 °C (potatoes/roots), each with regular visual checks.

In the kitchen these crops carry stews, oven trays, purées, and doughs; combined with legumes and leafy greens they form complete, balanced meals—the backbone of a resilient yearly plan.

Potatoes

Usable target: ≈ 220 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 260–330 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 6.5 kg/m² → ≈ 34 m²Sweet potatoes

Usable target: ≈ 195–200 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 240–300 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 2.5 kg/m² → ≈ 78–80 m²Winter squash

Usable target: ≈ 60 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 75–100 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 6.5 kg/m² → ≈ 13 m²Root vegetables (carrots, beets)

Usable target: ≈ 120 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 150–190 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 5.0 kg/m² → ≈ 31 m²

Protein and fiber

Protein isn’t just “building material” for muscles—it also forms enzymes and hormones, supports repair, and anchors satiety.

In the yearly pantry, beans, peas, soy, lentils, and sweet lupins do the heavy lifting; grains and quinoa complement the amino-acid profile, nuts and seeds round things off.

For reliable harvests, focus on sturdy trellises, weed-light rows during the first 4–6 weeks, even moisture through pod fill, and a legume-friendly rotation.

Harvest dry-ripe; then finish drying carefully, clean, and store in airtight containers in a cool place. In the kitchen, soaking, adequate cooking time, and fermentation (tempeh, sour beans, miso-style) improve tolerance.

Combine protein carriers deliberately with starches and vegetables: chili with beans and tomatoes, lentil stew with root vegetables, tofu with winter brassicas—complete, everyday meals emerge.

Dry beans (variety mix incl. field peas)

Target (usable): ≈ 65 kg/year (dry)

Energy/Protein: ≈ 3,400 kcal/kg → ≈ 221,000 kcal/year; protein ≈ 22 % → ≈ 14.3 kg

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 72–85 kg/year

Yield & area: row length ≈ 260 m; 50 cm row spacing → ≈ 130 m²Soybeans (for tofu/drinks)

Target (usable): ≈ 15–20 kg/year (dry)

Energy/Protein: ≈ 4,460 kcal/kg; protein ≈ 36 %

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 18–25 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 80 m²Lentils

Target (usable): ≈ 10 kg/year (dry)

Energy/Protein: ≈ 3,520 kcal/kg; protein ≈ 25 %

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 12–15 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 0.12–0.18 kg/m² → ≈ 70–100 m²Sweet lupins (sweet cultivars only)

Target (usable): ≈ 12 kg/year (dry)

Energy/Protein: ≈ 3,700 kcal/kg; protein ≈ 38 %

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 14–18 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 0.25–0.35 kg/m² → ≈ 50–70 m²

Leafy, brassica, and storage greens

Leafy vegetables provide the daily freshness window: vitamin K, folate, vitamin C, secondary plant compounds, plus minerals like calcium and magnesium.

For a continuous flow, work on two tracks. Quick growers (lettuce, spinach, Asian greens, purslane, chard) in sowings every 2–3 weeks. Long-season crops (kale and Brussels sprouts, white and red cabbage, leek) on their own rows.

Key are loose, humus-rich soils, mulch for steady moisture, fine-mesh nets against flea beetles and cabbage whites, and good airflow to prevent disease.

Herbs such as parsley, chives, dill, coriander, mints, and thyme raise nutrient density and flavor with minimal footprint.

For winter security use fermentation (sauerkraut, kimchi), freezing of blanched portions, and storage cabbages so the plate stays colorful even while beds rest.

Quick-growth block (lettuce, spinach, chard, purslane, herbs)

Usable target: ≈ 70–85 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 85–120 kg/year

Yield and area: ≈ 2.0–3.0 kg/m² → ≈ 35–40 m²Kale

Usable target: ≈ 40–45 kg/year

Yield and area: ≈ 1.6–2.2 kg/m² → ≈ 22–28 m²Brussels sprouts

Usable target: ≈ 10–15 kg/year

Yield and area: ≈ 1.5–2.0 kg/m² → ≈ 6–10 m²Leek

Usable target: ≈ 20–25 kg/year

Yield and area: ≈ 2.5–3.5 kg/m² → ≈ 7–10 m²White cabbage (for sauerkraut)

Usable target: ≈ 40 kg/year

Yield and area: ≈ 3.5–5.0 kg/m² → ≈ 8–11 m²Red cabbage

Usable target: ≈ 20 kg/year

Yield and area: ≈ 3.5–5.0 kg/m² → ≈ 4–6 m²Onion and garlic crops

Usable target: ≈ 60–65 kg/year (excl. leek)

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 75–90 kg/year

Yield and area: ≈ 5.0 kg/m² → ≈ 13–16 m²

Split guide: onions ≈ 48–52 kg, garlic ≈ 12–14 kg

Note: Stagger onions via sets/seed for spring–summer + storage onions. Plant garlic in autumn for robust bulbs; spring plantings supply extra cloves.

Sauce, oven, and summer vegetables

This group supplies the aromatic base for many everyday dishes—from passata and pepper ragù to oven trays, pickles, and ferments.

Warm-loving crops like tomatoes, peppers, zucchini, cucumbers, eggplants, corn, tomatillos, and (optionally) okra benefit from warm, sheltered beds, mulch for even soil temperature, root-zone irrigation (not over the leaves), and good airflow.

Trellises and rain protection (tomato roofs/hoops) reduce disease pressure; adequate calcium and steady moisture prevent blossom-end rot.

For the pantry, use canning (passata, sauces), fermentation (cucumbers, peppers), roasting and freezing (peppers, zucchini cubes), drying (tomato chips), plus vinegars and chutneys.

Because processing reduces weight, the raw amounts below are sized so realistic kitchen quantities of finished sauces and preserves remain. Variety in cultivars (early–late, firm–juicy, mild–hot) and staggered planting dates ensure a continuous harvest flow and ease processing peaks.

Tomatoes

Targets: ≈ 35–40 kg fresh plus ≈ 45–55 kg passata

Derived raw amount: ≈ 110–120 kg/year (≈ one third fresh, ≈ two thirds sauce; ≈ 60% yield)

Yield & area: ≈ 4.0 kg/m² → ≈ 28–30 m²Peppers and chiles

Targets: ≈ 12–16 kg finished roasted/sauce product per year

Derived raw amount: ≈ 18–22 kg (≈ 75% yield)

Yield & area: ≈ 2.0 kg/m² → ≈ 9–11 m²Cucumbers (salad and pickling)

Usable target: ≈ 40–50 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 50–65 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 3.0 kg/m² → ≈ 15–18 m²Fresh bush/pole beans

Usable target: ≈ 35–45 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 45–60 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 1.5–2.0 kg/m² → ≈ 22–30 m²Sweet corn (as vegetable)

Targets: ≈ 50–60 ears/year (≈ 10–12 kg edible portion)

Yield & area: planting density ≈ 0.25 m²/plant → ≈ 12–15 m²Tomatillos

Usable target: ≈ 15 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 18–22 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 2.5–3.0 kg/m² → ≈ 6–8 m²Celery, stalk

Usable target: ≈ 15 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 18–22 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 3.0 kg/m² → ≈ 5–6 m²Zucchini

Usable target: ≈ 40–60 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 7–10 kg/m² → ≈ 6–8 m²Eggplant

Usable target: ≈ 15–20 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 2.5–3.0 kg/m² → ≈ 6–8 m²Okra (optional)

Usable target: ≈ 8–10 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 1.0–1.3 kg/m² → ≈ 8–10 m²

Grains and pseudograins

This crop group supplies a large share of base calories and baking/pasta quality, but it requires substantial area and downstream processing.

Field work and harvest are weather-sensitive; afterwards come drying, threshing, cleaning, and milling or flaking.

For a reliable year’s supply you’ll need dry, cool storage; pest-tight containers; a small grain mill; and—depending on use—an oat flaker.

Species and cultivar choice affects the workflow: hull-less oats save dehulling; quinoa requires washing off saponins.

Rotations with legumes improve soil fertility and reduce disease pressure; straw can be used as mulch or bedding.

The areas below are sized so that, despite typical field and processing losses, realistic kitchen quantities for bread, pasta, and sides are produced.

Targets (example mix): total flour 120 kg/year → wheat 90 kg (of which 20 kg for pasta), rye 30 kg; flakes: oats 40 kg/year

Derived grain amounts (with losses): wheat flour 90 kg ⇒ net grain ≈ 125 kg ⇒ ≈ 163 kg; rye flour 30 kg ⇒ net ≈ 42 kg ⇒ ≈ 54 kg; oat flakes 40 kg ⇒ ≈ 52 kg

Yields & areas: wheat ≈ 0.35 kg/m² → ≈ 467 m²; rye ≈ 0.25 kg/m² → ≈ 218 m²; hull-less oats ≈ 0.21 kg/m² → ≈ 249 m²

Total grain area ≈ 934 m²Quinoa

Usable target: ≈ 15 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 18–22 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 0.30–0.45 kg/m² → ≈ 40–70 m²Naked oats for yogurt

Target: ≈ 3 L/week → ≈ 15–16 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 18–22 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 90 m²

Fat and seed sources

Seed crops provide concentrated energy, high-quality fats, and complementary protein as well as vitamin E, magnesium, zinc, and selenium.

Particularly valuable is the omega-6 to omega-3 balance: hemp and flax supply the omega-3 precursor ALA, while sunflower seeds contribute vitamin E and mostly monounsaturated fats.

Cultivation and use follow a simple rule set: sunny, well-drained beds; clean harvest; thorough drying to storage moisture; then store whole seeds dark, cool, and airtight.

Whole seeds keep far longer than meal or hulled kernels; grind or hull as fresh as possible before use. Gentle toasting lifts aroma, but avoid dark roasting to limit oxidation.

Small hand presses can produce oil at home; the press cake remains a protein-rich kitchen ingredient.

In the field, give these crops wider spacing, control weeds in the first weeks, and place them in legume-rich rotations.

Sunflowers support pollinators; hemp is wind-pollinated and may require approved cultivars or permits depending on region.

For daily practice, small amounts are enough: up to two tablespoons per person over porridge, salads, vegetable dishes, or spreads—reliably improving fat quality in the overall diet.

Sunflower seeds

Usable target: ≈ 10 kg kernels/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 12–16 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 0.4 kg/m² → ≈ 25 m²Hemp seed

Usable target: ≈ 10 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 12–15 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 0.35–0.50 kg/m² → ≈ 30–40 m²

Note: Industrial hemp often requires approved varieties/permits.Flaxseed (optional)

Usable target: ≈ 6–8 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 8–10 kg/year

Yield & area: conservative ≈ 0.10–0.20 kg/m² → ≈ 40–80 m²

Note: Typically low-yield in home gardens; valuable as an ALA source—alternatively buy flaxseed oil.

Berries, fruit trees, and nuts

These perennials stretch the harvest season, raise micronutrient density (vitamin C, K, folate, polyphenols), and provide fruit that stores or processes well.

They permanently occupy space but are relatively low-maintenance compared with annual crops.

For planning and care, focus on site-appropriate cultivars, pollination partners, frost pockets, wind protection, soil reaction, and access to irrigation.

Berry hedge

The goal is a year-round berry axis for fresh eating, freezing, ferments, jellies, and vinegars.

Total target (usable): ≈ 100 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 120–160 kg/year

Area and planting: 25–40 shrubs as a hedge or espalier, 1.2–1.8 m spacing → ≈ 45–55 m² linear bed area

Mix guidelines:

Black/red currant 8–12 shrubs, 2.5–4.0 kg each/year

Gooseberry 4–6 shrubs, 2.0–3.0 kg each/year

Raspberry 6–10 canes, 2.0–3.0 kg each/year

Blackberry 2–4 canes, 4.0–6.0 kg each/year

Highbush blueberry 4–6 shrubs, 1.5–3.0 kg each/year (acid soil, mulch)

Optional aronia/rowan for juice and vinegar

Strawberries

Separate block, because culture and renewal differ from shrub berries.

Usable target: ≈ 30 kg/year

Derived harvest (with losses): ≈ 40–55 kg/year

Yield & area: ≈ 1.2–1.5 kg/m² → ≈ 20–25 m²

Notes: three-bed renewal system; companion planting with garlic supports plant health

Fruit trees

Semi-dwarf rootstocks offer a good compromise of yield, anchorage, and handling.

Target mix and planting number: 2 apples as the backbone, plus 1 each of pear, sour cherry, plum/damson, quince; optionally 1 peach/nectarine at a warm wall

Target yield total: ≈ 120–160 kg/year at full bearing

Typical per-tree ranges (mature stands; variety and site dependent):

Apple (semi-dwarf) 25–50 kg

Pear 20–40 kg

Sour cherry 15–30 kg

Plum/damson 20–35 kg

Quince 15–25 kg

Peach/nectarine 10–25 kg in good yearsArea: crown spacing 3–4.5 m; mulch the root zone → ≈ 40–50 m² for the mix above

Notes: secure pollination; spindle or espalier saves space; plan storage for autumn/winter fruit

Nuts

Long-term sources of fats, calories, and minerals with modest care needs, but a later start to bearing.

Hazel (2–3 bushes): target ≈ 6–10 kg/year in shell; spacing 3–4 m → ≈ 15–30 m²

Walnut (1 tree, if space allows): long-term ≈ 10–20 kg/year in shell; large crown → ≈ 40–80 m²

Optional chestnut: only where site-appropriate; yield strongly climate- and soil-dependent

Area summary

Total cropped area: ≈ 1,780–1,980 m²

Including paths, compost, water management, and work zones: +25% → ≈ 2,225–2,475 m²

From plan to practice

Self-sufficiency for two adults is feasible, but it is land-, time-, and processing-intensive. At the scale shown here you’ll need roughly 2,047–2,475 m² in total, including paths, compost, water management, and work zones—calculated for all of the crops above as one integrated system.

Important reality check

Soil assumption: Calculations assume a humus-rich, well-supplied, stone-poor soil with good water infiltration and distribution.

If that’s not the case: Expect lower yields in the first years and more land or labor for soil building, stone removal, organic fertilisation, mulching, compost management, and water control. Only with stable soil structure do yields approach the guide values.

Price in losses: 10–20% in the field and 5–20% in storage/processing are normal. Choose varieties, harvest timing, and storage logistics accordingly.

Smooth labour peaks: Stagger sowings, combine early/mid/late cultivars, plan rain protection and trellises, and schedule processing windows (canning, ferments, drying) in advance.

Scale stepwise: Start with 25–50% of the targets, record real yields, and adjust area, cultivars, and methods in year two.

The plan works when soil, water, storage, and processing are aligned. Then a reliable annual supply emerges from a stable calorie base, well-planned protein sources, fresh leafy and brassica greens, process-friendly summer crops, grains and pseudograins, and perennial berries, fruit, and nuts—an integrated system that keeps plates filled all year.

Sources

Sources

Yield ranges vary by region. For site-specific planning, consult local advisory/extension services and run small on-site variety trials.